Domestic workers organized some of the earliest labor unions, and Black women who knew the importance of workers’ rights stepped up to lead them. With Black History Month recognized in February and Women’s History Month coming in March, it’s fitting to look back on some of the notable Black women in the labor and civil rights movements.

Domestic workers organize and strike

Newly emancipated Black women started the first union in Mississippi history in 1866, sending a resolution to the mayor of Jackson detailing their plans to charge a “uniform rate” for laundry work. A few decades later, Black women in Atlanta followed in their footsteps, but were forced to take it even further with a strike.

At the start of the 1880s, 98 percent of Atlanta’s working Black women were employed as household workers, often paid low wages and putting in long hours.

“Domestic workers included the maids, child nurses, cooks, laundresses, and they engaged in the most intimate labor, the least desirable work conducted in the homes of white families especially in the South after emancipation and Black women overwhelmingly dominated these positions,” said Dr. Tera Hunter, author of “To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War,” during a question and answer with the Zinn Education Project. “They were paid substandard wages, were expected to work very long hours, to endure insults and even sometimes physical assaults to keep their jobs.”

Laundry work performed by “laundresses” afforded women some flexibility as they did the wash in their own homes and communities – but more importantly, it gave them solidarity that would fuel a coming labor movement.

In the summer of 1881, a group of 20 laundresses, fed up with unfair wages and lack of respect, formed a trade organization, the Washing Society, to fight for higher pay, respect, and autonomy over their work. Support grew quickly, with the 20 members climbing to 3,000 in only three weeks of door-to-door organizing.

The striking workers faced arrests, fines and hostile visits from Atlanta officials, who employed scare tactics to try and defeat the strike.

“When the strike broke out in July, the women faced a lot of opposition and ridicule,” Hunter said in the video. “From employers, from city officials, from businessmen and the most vocal was the local newspaper, the Atlanta Constitution. But opponents who laughed initially were soon forced to admit that the nickname they gave these women, the Washing Amazons, actually proved to be more symbolic than derisive in terms of showing their effectiveness.

“What’s remarkable is that this was a group of marginalized workers, mostly illiterate, women, and yet they organized the largest strike in the city’s history,” Hunter said. The laundresses’ strength and determination in the face of opposition inspired other Black workers in the city to demand higher wages and better conditions. “The washerwomen are an important reminder of the role that working class women have played in grassroots politics in the South and elsewhere.”

Women leaders in union organizing

As Black women dominated the ranks of domestic workers, it’s no surprise that they also led the charge for fair wages and respect among the workforces.

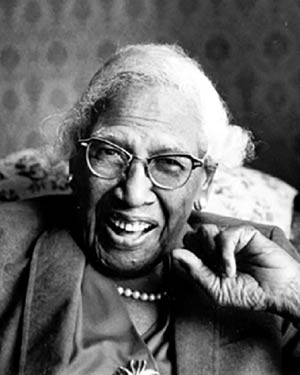

Photo by Dwight Ross, Jr., Courtesy Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive (AJCP330-041ac)

Dorothy Lee Bolden started off as a civil rights activist, but in 1968, she helped organize the National Domestic Workers Union of America. While it wasn’t a formal union, it brought together women in the industries and at its height served more than 10,000 members.

“Bolden’s leap from bus passenger to leader of a powerful labor organization was not far-fetched to those who knew her,” according to her obituary in The New York Times, published as part of a series of obituaries for Black men and women who had been overlooked at the time of their deaths. “She had already taken part in the civil rights movement, marching in protests alongside figures like the late Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), who led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s. ‘She spoke up, and she spoke out, and when she saw something that wasn’t fair, or just, or right, she would say something,’ [Lewis] said in a telephone interview.”

Bolden was proud of her job as a domestic worker. In 1983, she told The Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution that “[a] domestic worker is a counselor, a doctor, a nurse. She cares about the family she works for as she cares about her own.”

Her advice for organizing?

“You have to teach each maid how to negotiate,” she said in “Household Workers Unite.” “And this is the most important thing — communication. I would tell them it was up to them to communicate.”

In the 1920s, Rosina Corrothers Tucker helped organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) with her second husband, Berthea J. Tucker, a Pullman porter. The trade union became the first Black labor union recognized by the AFL-CIO.

Using the skills she gained as an advocate for BSCP and as a founding member of the International Ladies’ Auxiliary Order, she worked tirelessly to organize laundry workers, domestic workers, and hotel and restaurant workers, jobs which were predominantly held by Black women. She was also a leader in the fight to integrate public spaces in Washington, D.C., and advocated for the rights of children and the elderly.

“Tucker’s contributions to labor and civil rights extended well beyond the BSCP,” according to the National Parks Service website. “In the early 1940s, she played an important role in the March on Washington movement, which challenged segregation in the armed forces and defense industry. She also organized locally in Washington, D.C., both to boycott businesses that refused to hire Black employees and to create unions for women working in the laundry and domestic service industries.”

In 1963, Tucker helped organize the March on Washington, the largest gathering for civil rights of its time with an estimated 250,000 people descending on Washington by plane, train, car and bus from across the United States.

The march was the brainchild of A. Philip Randolph, founder of the BSCP, but is perhaps most well-known for Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech.