Thieves broke into Luella Kenny’s house six times in the late 1970s to steal whatever they could find and nothing, including a full-size pool table, was too big for them to take. “They cleaned us out,” Kenny recalls. Her home in the now notorious Love Canal neighborhood of Niagara Falls was unsafe to live in after it came to light that it was contaminated by buried hazardous waste that had been dumped into a nearby unused canal.

Kenny is 85 now, and it’s been 44 years since the environmental disaster known as “Love Canal.” A PEF retiree, Kenny worked as a research scientist at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo. The nightmare is never far from her thoughts. Some people were crushed by it. Not Kenny. She is driven to help and save others from the horror of deadly pollution that flows through their water, blows through their air and contaminates their gardens and homes.

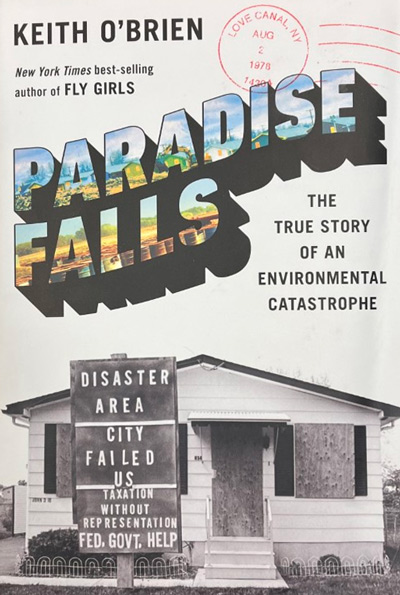

Her tragedy and that of more than a thousand of her neighbors is detailed painstakingly in a new book, “Paradise Falls,” by Keith O’Brien. The book follows the women who stepped forward to confront the environmental catastrophe — Kenny, Lois Gibbs, and many others. They spoke truth to power and in return received false promises and outright lies.

“They tried to give us lollipops all along the way,” Kenny said. “Sometimes when I am speaking at a group, someone will come up to me afterward and say, ‘I always hated having to lie to you.’”

Not every politician brushed them off. Congressman John LaFalce and his aide Bonnie Casper were among the first to take the situation seriously and work to help the residents. U.S. Senator Al Gore called the women and the polluters to Washington to testify. Gore took action despite his father’s membership on the Occidental Petroleum Board of Directors, when Occidental owned the company that polluted Love Canal, Hooker Chemical. And President Jimmy Carter was the one who ultimately made it possible for Kenny and the remaining residents to get out of harm’s way.

In May 1980, Kenny traveled to San Francisco to confront billionaire Armand Hammer, Occidental’s CEO, at its annual shareholder’s meeting and make them understand what Hooker Chemical had done. Not only had its dumping of industrial waste in the dry canal created the environmental nightmare, Hooker then sold the contaminated land to the local school district in 1952 for $1. The district built an elementary school and playground right over the dump. Sometimes children playing there were burned when they disturbed rocks that burst into flames.

In May 1980, Kenny traveled to San Francisco to confront billionaire Armand Hammer, Occidental’s CEO, at its annual shareholder’s meeting and make them understand what Hooker Chemical had done. Not only had its dumping of industrial waste in the dry canal created the environmental nightmare, Hooker then sold the contaminated land to the local school district in 1952 for $1. The district built an elementary school and playground right over the dump. Sometimes children playing there were burned when they disturbed rocks that burst into flames.

Kenny still travels the country speaking to groups who want to learn about America’s first large-scale environmental nightmare and how ordinary people can fight back. Not everyone agreed with her position at the time. She recalls walking with a government official when one of her neighbors ran up to them shouting, “Nothing is wrong here! There is no problem!” The woman who said that later “died of cancer, and so did her 19-year-old son,” Kenny remembers.

Gibbs and Kenny kept forcing the issue into the news and demanding that the state or federal government help them escape their homes that no one would buy. Hooker Chemical had dumped 20,000 tons of toxic waste, which included massive amounts of deadly carcinogens such as dioxin, toluene and benzene, from 1941 to 1952. But it wasn’t just the miscarriages, still births, birth defects, cancer, renal and neurological disorders that plagued residents of Love Canal. Their minds and spirits suffered too.

“The suicide rate was enormous,” Kenny recalls, “even one whole family.” Families and marriages fractured under the intense strain that went on for several years.

Kenny‘s marriage survived, but the youngest of her three boys, Jon Allen, died in October 1978 after being repeatedly hospitalized, sometimes for months, and without a diagnosis. He had just celebrated his seventh birthday.

Kenny, who began her state service (Roswell was operated by the state Health Department back then) in 1958 and officially retired in 1998 to care for her husband when his congenital heart problem worsened, returned to work part-time after his death, and finally stopped working in 2009. She was a PEF steward and a member of the joint health and safety committees at both the state Health Department and at Roswell Park. The Love Canal crisis peaked in 1978-1980, at the same time PEF was being organized and founded statewide.

“I never mentioned that I worked for the state Health Department when I talked about Love Canal,” Kenny said. It was a strategy that helped her avoid the retaliation that another Roswell scientist, Beverly Paigen, experienced when she became interested in Love Canal and started researching how the chemicals were leaching and flowing through old streambeds or “swales” that existed before the neighborhood was built.

One of the streams, Black Creek, flowed right behind Kenny’s house and her children often played in it, until the stench and obvious pollution forced them indoors. Kenny started collecting water samples on a regular basis and one day she saw a little bird alight next to the stream. She watched it hop into the water and take a drink. It dropped over dead.

Paigen and her husband, who was a manager at Roswell Park, did not live in the Love Canal neighborhood, but her research was neither welcomed nor accepted by Dr. David Axelrod, who was the state health commissioner at that time. And New York Governor Hugh Carey didn’t like anything or anyone who focused on the disaster. The hostility that Paigen’s research engendered finally convinced her and her family to leave and build new careers in California.

When the federal government finally stepped in and bought Kenny’s home so they could leave, they moved to Grand Island in the Niagara River and she lives there still. Kenny’s efforts resulted in Niagara University inducting her into its “Justice House” in May 2022.

“I overheard one woman say she thought I was getting rich off of it. That’s not true. Can you imagine living with your kids for two months in a hotel? It’s not conducive to family living. Or moving in with your mother-in-law in a four-room house? Everything I did and I do now is to prevent another child from losing its life to chemical or radioactive contamination,” Kenny said. “People need to know what they are up against.”