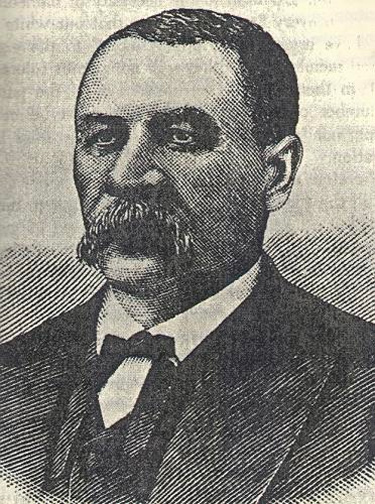

The name Frederick Douglass is well known. But what about Isaac Myers?

Douglass and Myers have several things in common. Both were caulkers in the Baltimore shipyards. Both were leaders in their respective movements – Douglass as an abolitionist and Myers as an early leader in the African American labor movement.

Organizing on the docks

In 1838, African American workers at the Baltimore shipyards formed the Caulkers Association, one of the first African American trade unions in the United States. The union helped bring about better pay for its members – so much so that it caught the attention and the anger of white coworkers on the docks.

As the situation soured, white workers struck in 1865, forcing shipyard owners to fire their African American workers. More than 1,000 were let go. While Myers wasn’t on the docks at the time, he kept in touch with many of his former coworkers.

Using his experience in the business world as a high-ranking clerk at a wholesale grocery business, Myers organized a group of African American and white business owners to create a new shipyard in 1866 that functioned as a cooperative.

The Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company employed more than 300 African American workers and Myers served as a board member until the company lost its lease and shuttered in 1884.

Taking the movement further

Myers ramped up his involvement in organized labor following that setback. In 1868, he was president of the Colored Caulkers’ Trade Union Society of Baltimore and began outreach to African American labor leaders in surrounding cities and in other trades, seeking to gain them entrance into the growing National Labor Union (NLU).

At the NLU’s 1869 Convention, Myers and a delegation of African American labor leaders addressed the session and made the case for equal treatment and acceptance of black leaders.

“I speak today for the colored men of the whole country … when I tell you that all they ask for themselves is a fair chance; that you shall be no worse off by giving them that chance …. The white men of the country have nothing to fear …. We desire to have the highest rate of wages that our labor is worth.”

The impassioned plea was discussed for two days among Convention delegates, but ultimately rejected. Myers and his fellow unionists didn’t let that defeat define them and immediately began organizing again – this time into the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU). In the final days of the CNLU, Myers launched the Colored Men’s Progressive and Cooperative Union, which despite its name admitted women, and advanced membership to workers without regard to race. It was a true industrial union that welcomed members of all occupational backgrounds.

Both the NLU and the CNLU folded during the 1873 Depression.

A lasting impact

Myers went on to become involved in the Republican Party under Abraham Lincoln and served as a Customs Service agent and a postal inspector, before returning to Baltimore in 1880 to operate a coal yard. He served as a leader of several community organizations, and was editor of the Colored Citizen, a weekly newspaper. He died in 1891, at the age of 56.