January 30, 2024 — Throughout the history of the labor movement in the United States, there are moments when Black workers, fed up with working conditions, lack of benefits and low pay, took steps to not only create new unions, but lead labor in the fight to secure better quality of life for workers.

One of the first unions to exist solely for Black workers formed in 1869. Despite then National Labor Union (NLU) President Willian Sylvis agreeing that there should be “no distinction of race or nationality” within the union, many unions still excluded Black workers. Several Black delegates attended the annual meeting of the NLU in 1869 to speak for solidarity and ask white members and Black members to fight together. When white members refused to see them as equals, the Colored National Labor Union was formed, with Isaac Myers as its first president.

Despite their hard work trying to improve the lives of their members, as well as petitioning Congress to assist Black farmers in the South, the CNLU eventually disbanded and became more of a political entity than a labor union. However, their work to show the strength of Black workers helped to advance the cause of labor union desegregation.

The Knights of Labor was one of the first unions to not only open to Black and women workers in the United States, but also the first to understand that excluding certain workers could give employers a tool to undermine the union and build that solidarity into their strategy. In 1886, about 75,000 Knights members were Black or a woman, making accounting for about 10% of the membership.

Although many predominantly Black unions had risen and fallen over the years, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, led in 1925 by A. Philip Randolph, was the largest union of Black members to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL), now known as the AFL-CIO.

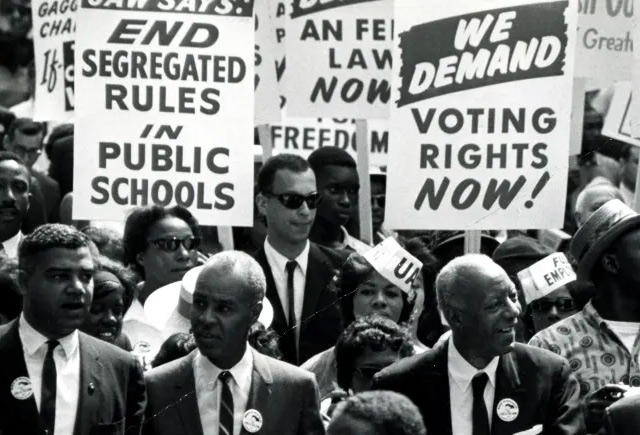

Randolph was a well-established labor leader and fought for more than 40 years on behalf of workers. His most important work as part of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was to make sure that as America entered World War II in the 1940s, Black workers were able to find work in factories and at shipyards. As a result of threatening a march on Washington, D.C., of 50,000 Black workers to protest exclusion from production jobs, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which banned “discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

President Roosevelt also established the Fair Employment Practices Committee to enforce the order. Though the committee would later be dissolved by Congress, it laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission following the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Today, after many mergers over the years, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters is part of what is now known as the Transportation Communications Union (TCU).

For his part, Martin Luther King, Jr. encouraged and supported more than 1,000 Black workers from the Memphis Department of Public Workers when they went on strike in 1968. The strike was spurred on by the death of two Memphis garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, who were crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck. Despite petitions and actions to try and remove the malfunctioning trucks and otherwise improve workplace safety, the then mayor of Memphis, Henry Loeb, refused nearly every request by the workers.

King rallied with the sanitation workers throughout the duration of the strike, which lasted from February to April of 1968. Some of the protests became violent due to outside actors and Mayor Loeb responded by calling on the National Guard. Still, King held to the movement, and on April 3, 1968, he delivered his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” address to the workers.

The following evening, April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated. In response to the unrest in Memphis and Mayor Loeb’s stubborn attempts to block the union, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson tasked Undersecretary of Labor James Reynolds with negotiating on behalf of the union and the mayor to end the strike.

With the help of Reynolds, and 42,000 silent protestors led by King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, success was finally within reach. Loeb and the Memphis City Council reached a deal with the union to recognize it and guarantee better wages for workers on April 16, 1968.

This Black History Month, PEF remembers these moments and realizes our movement stands on the shoulders of Black labor leaders who paved the way. We must heed the words of U.S. Representative Yvette Clarke, who said during Black History Month: “We must never forget that Black History is American History. The achievements of African Americans have contributed to our nation’s greatness.”